Recently, I visited with a man named Lamont, a prisoner at Menard Correctional Center. He’s 34 years old and grew up in Chicago. Lamont is Black. Lamont was first diagnosed with a serious mental illness at the age of 10. As a child, he was diagnosed with bipolar disorder, post-traumatic stress disorder, and depression. He was hospitalized for these conditions as a child.

As a teen, he became involved in the gang life. After several brief stints in prison for drugs and a battery charge, he was charged with murder. His lawyer complained that he was asked to do too much work, and Lamont says the man never even contacted the three witnesses Lamont gave him—witnesses who would have testified that Lamont did not commit the murder. Lamont was convicted and given a 75-year sentence, with no consideration at all given to his lengthy mental health history. Unless the law changes, or he is pardoned, he will die in prison.

The “new” cellhouses at Menard were completed in the 1920s. Since then, the biggest changes have been that most cells, designed for one person, now house two people.

Despite his mental health issues, until July 2014 Lamont had a clean disciplinary record. He was regularly seeing mental health professionals, and was taking several psychotropic medicines. These treatments were helping him cope with his disease and the stresses of prison. Lamont was doing well enough that he was given a plum job assignment working in the inmate kitchen, preparing meals for the other prisoners. This job is reserved for the best-behaved prisoners, since they are working with knives and other potential weapons.

Then on July 3rd, one of the officers in the kitchen was using racial slurs (something that happens virtually every day at Menard), and referred to Lamont as a “n**ger.” Lamont exploded, and when the officer escalated the conflict, Lamont stabbed him. Lamont was written a disciplinary report. However, rather than recognize that the altercation resulted from the officer’s abusive language, and without any consideration being given to his mental health history, Lamont was charged with unauthorized organizational activity—a charge usually reserved for gang activity. But in this case, a Black man objecting to being called a racial slur was enough to convict him. Instead of a year in solitary confinement (the maximum penalty for striking an officer), Lamont was placed in indefinite solitary.

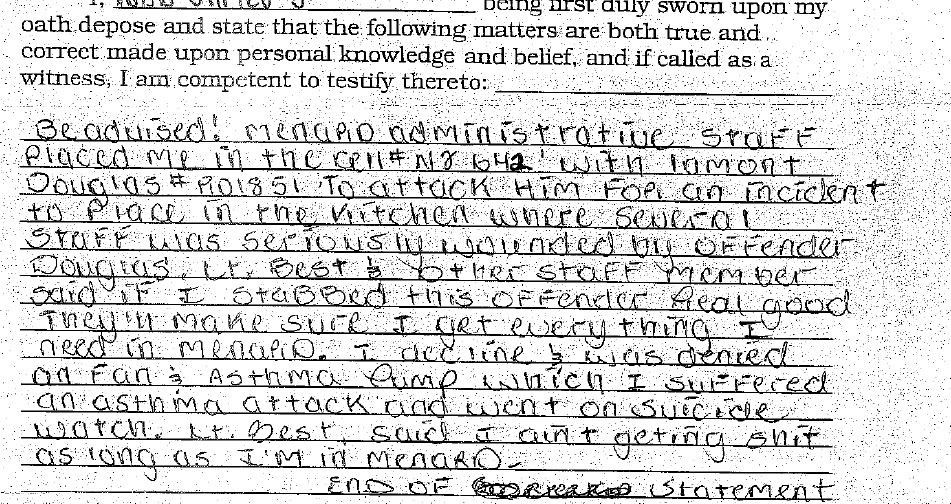

Confined to his cell 24 hours a day, he was subjected to continuous harassment by the guards, who flat out told him that they would make his time at Menard a “living hell” because of what he did. Guards attempted to bribe Lamont’s cellmate. They promised his cellie anything he wanted if he would stab Lamont. When his cellie refused, guards took his inhaler away, and he suffered an asthma attack.

In solitary, Lamont’s mental health problems became much worse. He began taking a number of psychotropic medications, and saw a mental health worker weekly. However, guards would regularly insist that they had to stay in the room during his therapy sessions, and would then talk about his issues in front of other prisoners, causing Lamont much distress and embarrassment. His mental health worker said she had no control over security.

Then, in March of 2016, Lamont was on the way to see his mental health counselor when guards took him into a room in the North Cellhouse where he was housed, and beat him while he was cuffed. The guards said, “This is what you n**gers get for trying to fight back.” His mental health counselor could hear Lamont screaming, but did nothing to intervene.

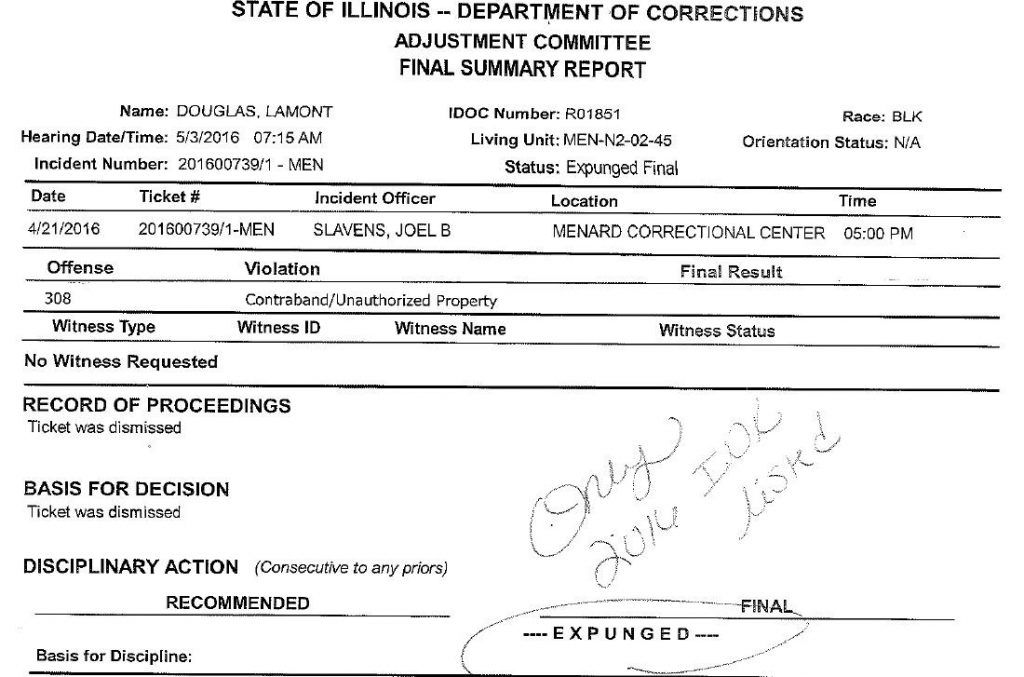

In April, guards alleged that he had “excess property” in his segregation cell. Rather than follow procedure and simply confiscate the unauthorized property, guards took all of his property, leaving him buck naked in a bare cell. Even though he was found not guilty of having excess property, to this day, much of his property, including books, trial transcripts, and other legal paperwork, has never been returned.

Lamont has now stopped going to his mental health appointments, because he lives in fear of again being attacked by guards. He has thus been cut off his mental health medications, and his mental health is deteriorating. He filed grievances, but they have all “disappeared”—even those he gave to his mental health worker to hand in for him. Lamont filed an appeal to the director of IDOC, but his appeal was returned, with a note that he had to get a response from Menard before he could appeal. He has asked for the forms he needs to file a civil rights case in court, but the guards refuse to give them to him.

Lamont has very little family support, and feels completely isolated, abandoned, and vulnerable. He needs a transfer to another prison, where he can escape the constant harassment he has been subjected to, and can get treatment for his deteriorating mental health. It was precisely because of people like Lamont that we filed our class action case Rasho v. Baldwin, which over the next three years will work to improve mental health treatment for every prisoner in the Illinois Department of Corrections.