To commemorate UPLC’s 45th anniversary, we have been sharing parts of our history. UPLC began as the legal arm of community organizing that was happening in Uptown. We have now refined our areas of work down to three: prisoners’ rights, Social Security disability, and tenants’ rights. But at one time, UPLC was a kind of “one-stop shop” for anyone in Uptown with any kind of legal issue.

Because of this, when people from Uptown went to prison (and plenty did, because the neighborhood had lots of poor and/or Black and Brown people, who are disproportionately affected by the criminal legal system), they remembered UPLC. If their rights were violated in prison, they reached out to us for help. UPLC considered people in prison to still be part of the community, so we helped them.

Terrell Walters was Black, grew up in housing projects in Chicago, and was sent to prison at age 16. Joe Ganci was white and (according to the Illinois Department of Corrections) was the founder of the “Northsiders”—an allegedly white supremacist gang. He once escaped from Cook County jail and made it all the way to the Bahamas, but was caught by the FBI when he returned to Florida. Both of these men were very disliked by Illinois Department of Corrections (IDOC) officials because they stood up against the inhumane conditions in the prisons. They were both held in Joliet prison, and in an attempt to silence them the prison literally walled off the end of a tier, placing just the two of them in this isolated area, hoping that the white racist and the Black Power guy would kill each other.

Instead, they became friends and worked together to disrupt things at the prison, doing things like tying bed sheets together to yank out plumbing and flood the area. They wrote a letter to the Joliet newspaper about rat feces in the prison food. As a result, they were beaten by guards and tear gassed using tear gas meant for outside crowd control, not for indoor use. Guards even put up plywood to keep the gas in their cells. They both passed out as a result, and woke up outside, having been dragged out.

Both of these men had been charged with so many disciplinary violations that they had been punished with 100 years in solitary confinement (longer than either of their sentences). Joe, being from Uptown, reached out to UPLC about the tear gas incident. We found a pro bono attorney for him, and they settled.

Terrell and Joe then worked together to draft a complaint listing all of the things that were wrong at Joliet. However, Joe had no experience litigating federal cases, and Terrell only had approximately a third-grade education. Their handwritten, hard-to-understand complaint was dismissed by the judge, except one small claim. In a single paragraph they complained about lack of access to the law library due to being in solitary confinement. When the defendants announced that they were going to depose (ask questions under oath) Joe and Terrell, Joe recognized from his experience in criminal court that you should have an attorney when the state asked you questions. So, he reached out to UPLC again.

UPLC expanded their individual lawsuit to a statewide case. Our argument was that Illinois deprived people in solitary confinement from having meaningful access to the courts by not allowing them access to the law library, and not providing them with any other help they would need to understand how to file a complaint in court. And that’s a violation of the Constitution.

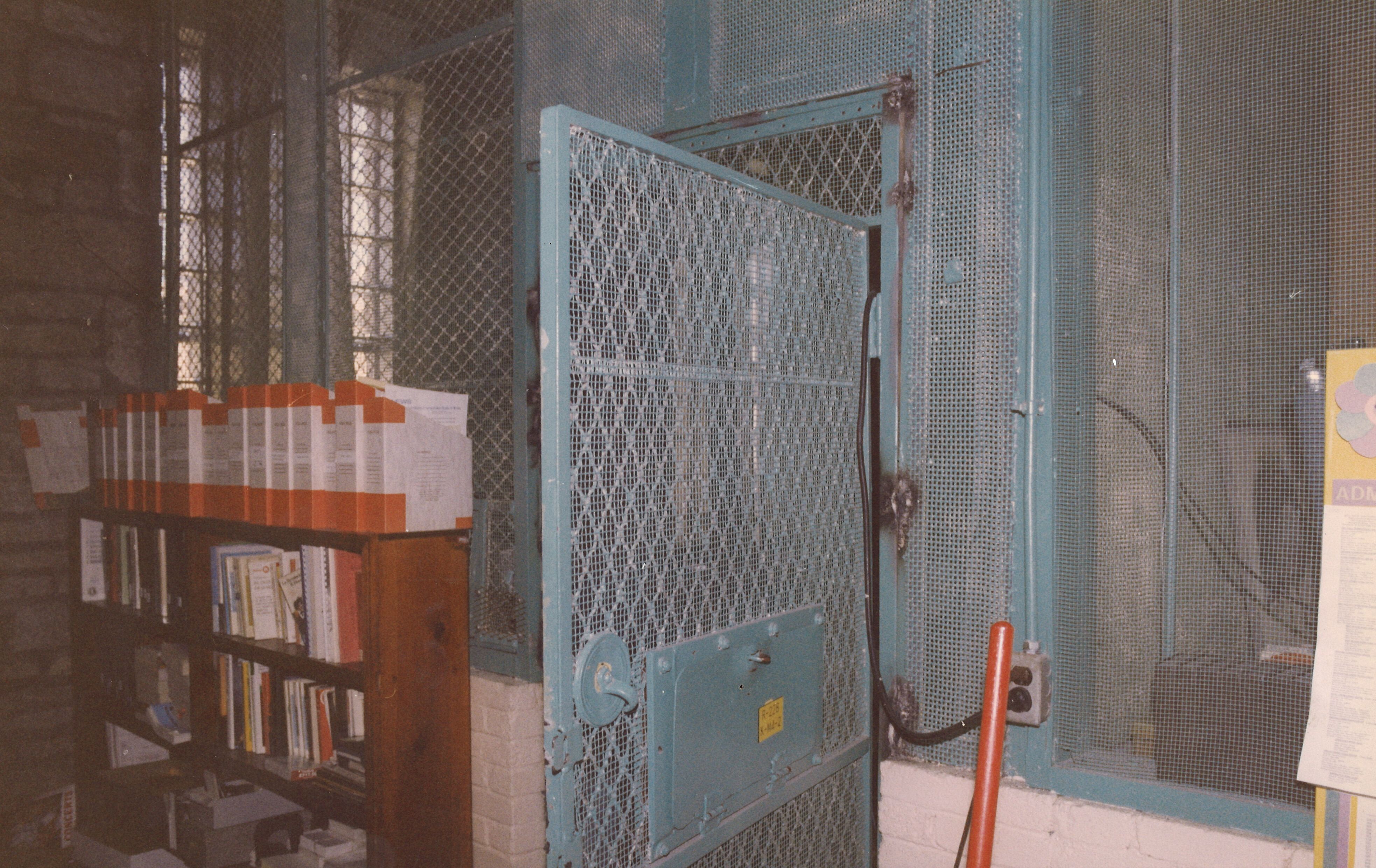

In prisons, law library clerks are uneducated, and not allowed to help prisoners do research or draft documents; they can only help find books. Prisoners who were in solitary confinement couldn’t browse books in the legal library and had to send requests for specific cases to the law library. Occasionally, they were brought to the library, where they had to sit in a cage and wait for someone to bring them a specific volume of cases they asked for. (See the photo of Joliet prison here.) Of course, this meant that they had to know specifically what book they wanted to read in order to request it.

UPLC and then-Board President James Chapman challenged this system in a class action lawsuit against the Illinois Department of Corrections that lasted 18 years. Three different judges said the current system was unconstitutional. However, as our case was pending, the United States Supreme Court ruled in an Arizona case that prisoners could not simply allege that the system was unconstitutional. Each individual plaintiff had to show they could have brought a specific case if they had been given help. Based on that new ruling, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals ruled that neither Joe nor Terrell had tried hard enough to get help, and thus never should have been allowed to bring the case in the first place. But the court went further and argued that no one could ever have standing, because if they could bring a case challenging access to the courts, then they obviously HAD access to the courts, because they brought that case–a classic catch-22 if there ever was one. The case was dismissed.

Some might think that devoting 18 years to a case that the courts ultimately ruled never should have been filed would have discouraged UPLC from representing prisoners. But it turns out that if you want to “advertise” in prison, an access to court case is a great way to do it because you get to know all the “jailhouse lawyers”—people inside who educate themselves on the law and help other prisoners with their cases. Because the jailhouse lawyers help so many people with their cases, word gets around. From this case, UPLC built a reputation among prisoners that lasts to this day. Not only do we receive thousands of letters each year from prisoners in Illinois, when our Executive Director Alan Mills tours the prisons, you can hear people calling out “That’s Alan Mills,” “Hey, Alan!” “Alan, come talk to me, I got a problem!”

It's thanks to the support of people like you that UPLC has carried on fighting for prisoners' rights for all these years. Thank you!